Intense Story-telling Studded with Surprises

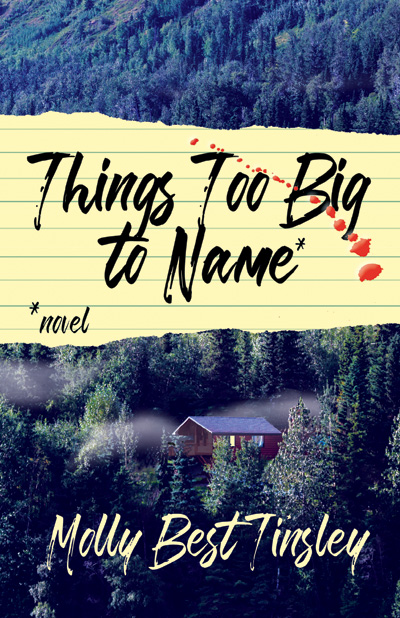

Fuze announces its latest release, a literary thriller by Molly Best Tinsley! Things Too Big to Name plunges into the mind of Professor Margaret Torrens when her planned rural retirement unravels and she’s forced to confront the life choices she’s made since the death of her musician husband years before. An early student, Jane Farrow, appears at Margaret’s mountain cabin with a strange child and asks to stay. Days later, disruption threatens violence when Victor Primo barges in looking for them. This distinctive braided narrative will keep you on edge until the end.

Author’s narrative: How Hearing Voice(s) Led to Publication

I wound up calling it a novel-in-progress because it kept resisting the confines of a short story. Changing its label did not make the path forward any easier. Ideas would present themselves, but when I pursued them, I’d slam up against a subject that felt like a dead end. A ghost, for example, when I didn’t believe in them; the pornographic industry and the criminal justice system, about which my pathetic ignorance might be impossible to hide.

Lugging my misgivings, I trailed the narrative all over the place, jotting notes, googling research, and worrying that after I died, someone would check my computer and conclude I was hooked on X-rated videos. Still, the manuscript file did grow, disorganized and unloved.

One day in the muddled middle, as I reread everything I had so far, I noticed I was hearing it inflected in my head. In other words, it had a voice. When further analysis actually identified three voices, I had the glimmer of order I needed. My protagonist was braiding three different stories, each directed to a different audience—a threatening stranger, her threatened self, and a lover whose death she’d never grieved.

The earliest draft of Things Too Big to Name grew out of a twilight collision between an automobile and a stag. The voice was formal, intelligent, deliberately neutral, as befit the driver, Margaret Torrens, an English professor who’d recently traded the city for a rural cabin. When Margaret gets back to her cabin after the accident, her husband appears, and though dead for decades, manages to pull her into a conversation that opened up their past. It pointed to something she was hiding.

Probing their brief life together unearthed a second narrative strand: Margaret’s private, emotional life began to speak. Its vulnerable, confessional voice evolved into love letters to a ghost.

Meanwhile, I’d hatched a new point of entry: Margaret has been locked in a cell undergoing psychiatric evaluation following an act of violence. This third story strand took the form of an interrogation, a tense game of cat-and-mouse. In the accounts she submitted daily to the psychologist, she had to sound like a reliable narrator, a model of accuracy and consistency. But her complex predicament left her with much to keep straight; thus this third voice emerged as daily notes to herself, jotted to restore balance after parrying her questioner. These notes required endless tinkering to get the voice right. They could not sound literary; they needed to be rough, fragmented, and yet coherent.

Here are three tips for sharpening narrative voice that emerged during my journey with Margaret: 1) Imagine a specific audience for the narrative. 2) Imagine your narrator’s purpose, her motives for telling a story: words not only say things, they do things–praise, rationalize, mock, confess, plead, mourn, you choose. 3) If you are writing in the third person, “limited omniscience” or “close third” has become a popular choice because it enables voice: the narrator speaks from the narrowed vantage of a character, whose attitudes, feelings, and intentions her voice can thus reflect.

This account of the crafting of Things Too Big to Name simplifies the process; it doesn’t really capture the inevitable nonlinearity. Margaret was prone to detours, into life with her husband, and his death, avoiding the week that led up to her incarceration. The psychologist was impatient to pry out the facts he wanted to hear. The competing time frames, with their differing access to information, kept me looping back to revise with every chapter forward. I suppose I should have devised a chart or something, but I tend to panic when faced with anything resembling a spreadsheet. Instead, voice became a light that pointed to where I was and what I could know.